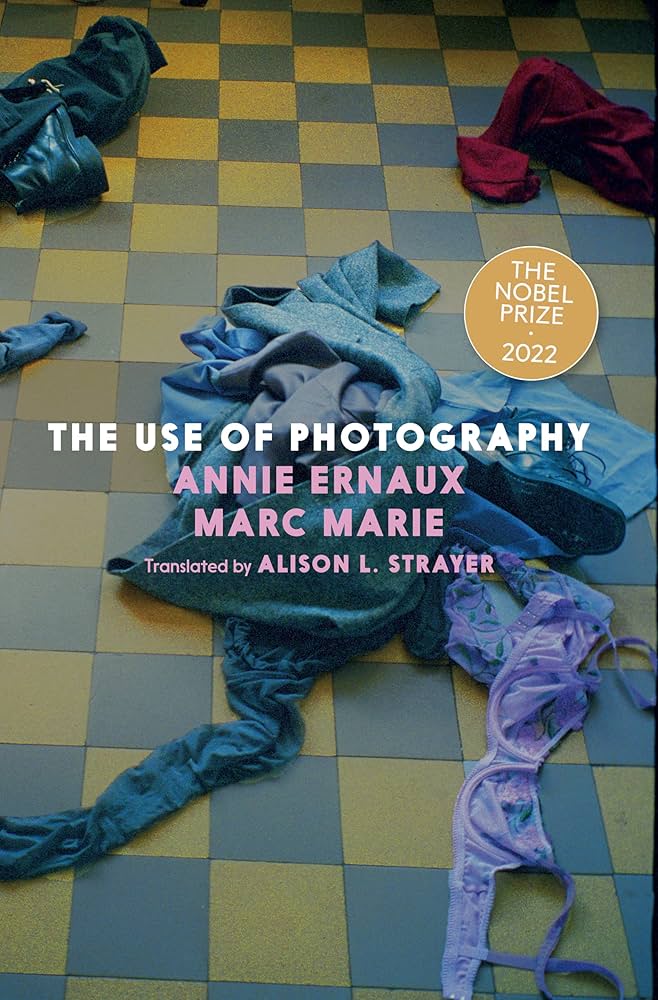

The Use of Photography is one of the most intimate and personal things I’ve read, and having read a few books by Annie Ernaux, that’s saying something.

The setup is novel: Ernaux and journalist Marc Marie began a relationship in 2003, and at some point, after each tryst they started taking a photo of the pile of clothes they abandoned. Then an unusual idea struck that forms the basis for the book:

We chose fourteen of the forty-odd photos and agreed that each would write separately, in total freedom, never show the other anything until it was done, or even change a word. The rule was strictly observed until the end.

The photos are personal but not scandalous or pornographic, and at the same time, it feels intrusive to linger on them.

From the New York Times review (gift link):

As images, they are the opposite of pornographic, leaving nearly everything to the imagination. They also have little in common with fashion photographs; in the couple’s rush to nakedness, the garments here are discarded with no regard for their display or preservation. In fact, Marie points out in an essay, these pictures resemble crime scene photographs. They attest to love’s sometimes violent needs, while also suggesting its eventual devastation.

The essays that follow are a couple of pages each, and usually start with a short description of the setting and circumstances leading up to the passion, from travel and glamourous events to Ernaux’s chemo treatments.

It’s a setup that’s bold and brave, and few writers would be able to do something like this without it feeling performative, or cringy or thirsty. This book isn’t any of those things. It’s incredibly intimate and at times uncomfortably straightforward.

Ernaux and Marie were not young lovers. She was undergoing chemotherapy for breast cancer at age 63 when the relationship began. Marie was a fan of her writing, and they had corresponded for a while before they became lovers.

The essays in The Use of Photography are often steamy, but also personal in other ways – Ernaux writes about mortality and cancer, about feeling undesirable because of how the chemotherapy affects her physical appearance. There are several essays that address her wigs — the chemo took all of her hair, and even with all of Ernaux’s fearlessness, she won’t be seen without a wig. Both authors show vulnerablility and introspection about what the relationship means.

And, becuase it’s Annie Ernaux, there’s ample discussion of art, literature, history and a dozen other topics. Her sentences are as original, thoughtful and memorable as ever.

Summer, by dint of the word that designates it in the French language – été – is always experienced as already over. Summer can only have been.

Marie keeps up with her, which is impressive. His writing isn’t as incisive or direct as hers, but his heart is all over the page. His affection for Ernaux is clear, he’s self-deprecating and humble.

He had ended his marriage shortly before this relationship began, and he’s open about what that means, his uncertainty about jumping into this relationship, and his own self-image.

This entire concept shouldn’t have worked. A couple near retirement age documenting their torrid love affair with photos of laundry shouldn’t be this compelling and life-affirming. But in Ernaux’s hands, even dirty laundry is riveting and alluring.