My dad died in January 2020. My mom is still going strong and in excellent health. But even discounting the pandemic, the first year after his death was extremely difficult for her. Her routines were upended. She kept talking to him even when she got past the ‘I forget he’s not here anymore’ part. She had to keep telling people that her husband had died, and since he was kind of a local fixture, it was never a short conversation. She still sleeps in a different room and almost never goes in their old bedroom.

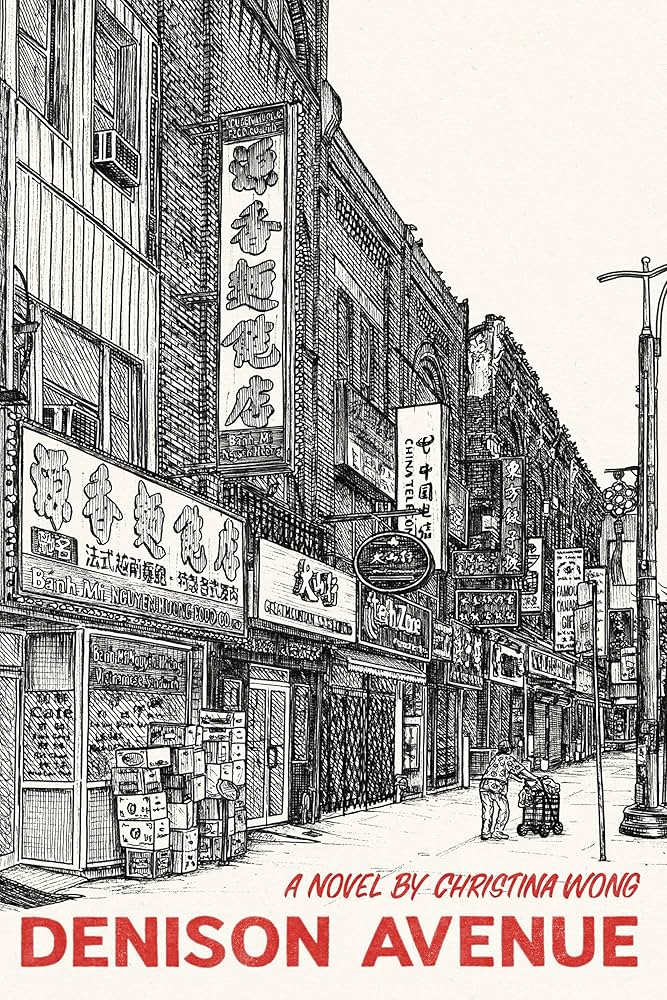

So while this book is an artful and memorable story about gentrification, race, class, and community, it connected with me most strongly as a story of a widow learning to keep going after her husband’s death. It brought me to tears a half-dozen times. It’s stylish and unique.

It’s a very simple story about a woman trying to get by after her husband’s death, in Toronto’s Chinatown, while remembering the decades they had there together. Her English is poor and the city around her is changing at a furious pace. It’s accompanied by about 80 pages of illustrations of locales in and around where the story takes place at various times.

It’s an instant classic as a Toronto Book. Like Scarborough, Scott Pilgrim, and a handful of books by Atwood (and surely a couple dozen others I haven’t found yet), familiarity with the setting makes the book much, much richer. Wong and Innes (in the illustrations comprising the flipside of the book) bring Kensington Market to life. The descriptions of the sounds and smells of the city connect on a visceral level. Narrator Wong Cho Sum’s recounting of the history of the area would have fit well in The Ward. Even the death of her husband is a perfect, awful Toronto thing.

And the way it’s written is unforgettable. Twice in the book, Wong does a thing where she runs two parallel columns of text, recounting the same experience at two different times of life, like a split-screen of two first times: the first time doing something with her husband, and the first time without him. It’s stunning stuff, and even just writing about it is emotional.

There are sections of text that are laid out like poetry, with line breaks and capitalization used in unexpected ways to create impact. And it does, boy does it ever:

But I know the time will come when I will no longer see you.

When you will become a shadow,

only seen when the light hits at the right moment.

The illustrations are outstanding. I spent a solid hour flipping these pages, and I’d hang some of the work on the wall given the chance. I have so many memories of the places Innes has drawn — some still there, some long gone. Innes has several pages where the same scene is drawn at different times, which can be particularly striking.

I read once about how reading literary fiction increases empathy. This book is a master class in that. If there was a Starter Kit for people moving to Toronto, this would be a key piece of it.

On top of that, it made me want to call my mom. So many lines in this book brought me back to conversations I had with her during the first year after my dad’s death, while she was figuring out what it means to be alone. On top of everything else, I think this made me understand her a little better.