This book broke my heart.

I’ve read a fair amount of McCullers’ writing in the past few months. Having read this biography one thing is clear: Carson McCullers wrote what she knew. That’s a devastatingly sad thing to say.

She herself was a tragic figure, struggling with her sexuality, alcohol, and being completely unprepared for the level of fame she reached in her early 20’s.

She was unlucky, getting strep throat at a young age in the era before easy treatment, which led to strokes and other health issues in her (short) adult life.

She was surrounded by enablers and abusers. Her husband was abusive, manipulative, and codependent. They seemed to bring out the worst in each other, mostly due to alcohol abuse.

She may have been sexually abused as a child. She was certainly taunted and let down by close family members because of her sexuality, and despite the fairly openly LGBT social circles she kept, her gender-neutral appearance and rejection of traditional femininity made her an outcast amongst much of society.

The list goes on, but you get the point.

In the collection of McCullers’ short stories I read a few weeks ago, the story that stuck out to me most was Who Has Seen the Wind. It’s about Ken Harris, a writer whose debut was a great success, and follow-up was a flop. It follows Harris over one night while he’s drinking himself into oblivion, threatening suicide, and destroying his marriage and friendships. He slowly gains awareness of the direness of his situation. There’s no hope or redemption in the story. It’s a brutal, depressing read.

Every aspect of this story has a parallel in McCullers’ life. She was never really able to achieve the success of her first novel, The Heart Is a Lonely Hunter. Her drinking alienated so many of her friends and supporters. Her husband and several other loved ones took their own lives. Her life after fame was characterized mostly by pain, emotional (alcoholism, failed marriage and friendship), physical (multiple strokes and disability issues), and professional (critical failures and difficulty writing).

McCullers found happiness at the end of her life, with a stable and healthy romantic relationship, solid friendships, and apparent sobriety. She died, apparently at peace, at age 50.

The book is a detailed and exhaustive account of her life. While Dearborn seems to have an outdated understanding of LGBTQ+ issues (she uses ‘sexual preference’ regularly, and spends a portion of the epilogue speculating about whether McCullers would be transgender if she was alive today), she has great empathy for her subjects. Even manipulative, abusive, codependent husband Reeves is treated in much the same way that McCullers treated her fictional characters — as flawed, well-intentioned, broken people, doing their best.

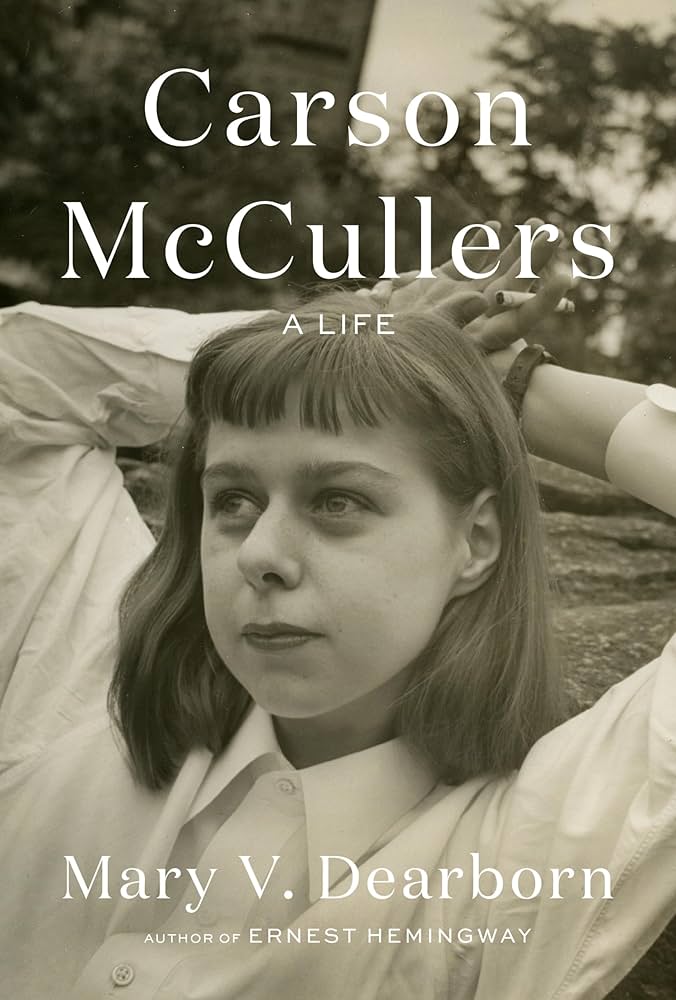

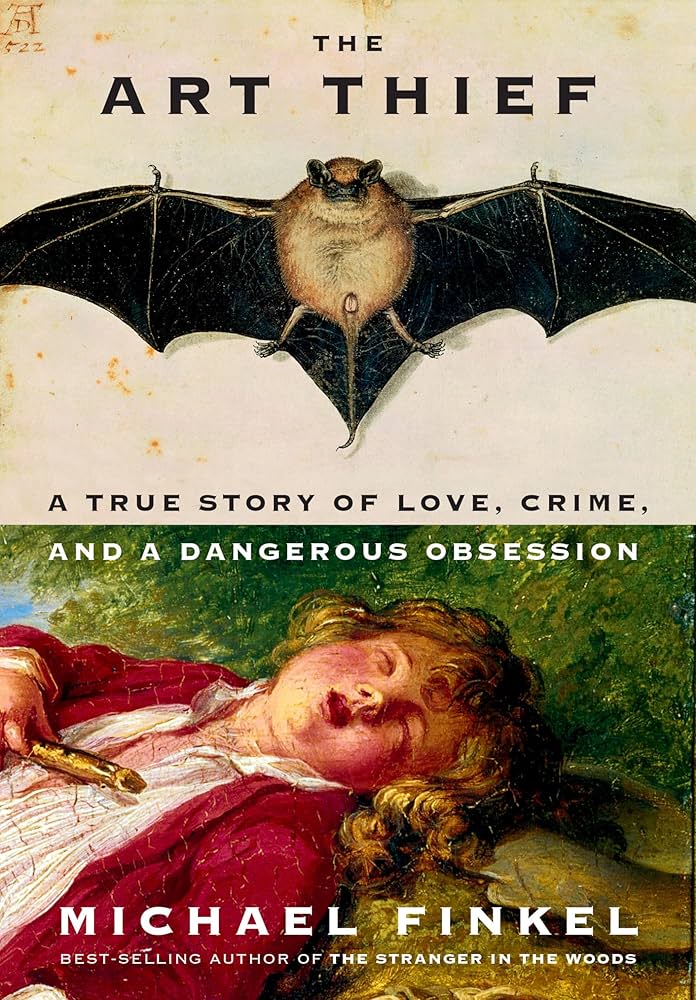

Dearborn’s biography is bookended by photos that bring me to tears, even a full day after finishing it: the cover shot, where a young Carson is young, healthy, and optimistic, and one of the last photos (on page 402), where she’s bedridden and about 70lbs, but looks ecstatic to be with her friend John Huston in Ireland.

If you’ve read anything by McCullers (and you should), this is a devastating, gorgeous and detailed look at how her life was reflected in her work.